DIY—or “Do It Yourself“—has always been more than a method of making music. It’s a cultural backbone that transcends sonic boundaries, embedding itself deep into the punk, hardcore, rock, and metal scenes around the globe. This movement didn’t ask for permission. It created its own venues, its own recording studios, its own fashion, its own laws.

In a world increasingly dominated by algorithms, consumerism, and corporate control, DIY stands as both a relic and a beacon—a call to self-organize, create from the ground up, and prioritize community over clout. This article traces DIY from its ragged roots to its modern metamorphosis, celebrating its resilience while confronting its current challenges.

Origins of the DIY Ethos: Punk Breaks the Mold

The ethos of DIY started long before punk, but it was the punk explosion of the 1970s that truly gave it a face—and a sound. Reacting to bloated arena rock and the gatekeeping of the music industry, punk was raw, immediate, and accessible.

In the United States, the early punk scenes in New York City found a home at CBGB, where bands like The Ramones and Television laid the groundwork. But the real heartbeat of DIY emerged in Southern California and Washington, D.C. Black Flag’s Greg Ginn started SST Records out of sheer necessity, crafting a homegrown label that would go on to release pivotal works from bands like Minutemen and Hüsker Dü. In Washington, D.C., Ian MacKaye and Jeff Nelson launched Dischord Records, initially to release Minor Threat’s work. Their label grew into a symbol of hardcore purity and ethical independence, embodying an anti-corporate stance that many would emulate.

Across the Atlantic, the United Kingdom’s punk movement was laced with politics and protest. Crass, a collective formed in Essex in the late 1970s, pushed the boundaries of DIY not just as a production method but as a lifestyle philosophy. They designed their own album covers, printed their own materials, and lived communally. The message was clear: reject commodification, embrace autonomy. DIY wasn’t just a tactic—it was an ideology embedded into every action.

Germany, still grappling with post-war identity, saw the rise of punk fused with the squatting movement. Berlin became a hotbed for radical self-expression. Collectives who believed in music as a form of resistance transformed abandoned buildings into venues. Bands like Die Toten Hosen and WIZO emerged from this landscape, carving their path without reliance on mainstream media or commercial infrastructure.

In Brazil, the punk scene of the early 1980s was as volatile as the political climate. São Paulo witnessed an eruption of energy as bands like Ratos de Porão and Cólera forged a path of resistance through music. Zines such as Punk Rock acted as the connective tissue for the scene, uniting fans, activists, and musicians under a shared cause. DIY in Brazil was born not just out of rebellion but as a survival mechanism within a society marked by instability.

Japan’s underground scene took a different form, blending precision with chaos. Bands like GISM and Gauze carved out a subculture that was as fiercely independent as it was insular. Tokyo’s underground shows were often held in cramped, nondescript clubs, promoted through flyers handed out at other gigs or by word of mouth. The culture was built on respect and ritual as much as on defiance.

Bands and Individuals Who Defined DIY

DIY wouldn’t have flourished without the visionaries who embodied its principles in both music and life. These individuals became the scaffolding upon which entire scenes were built.

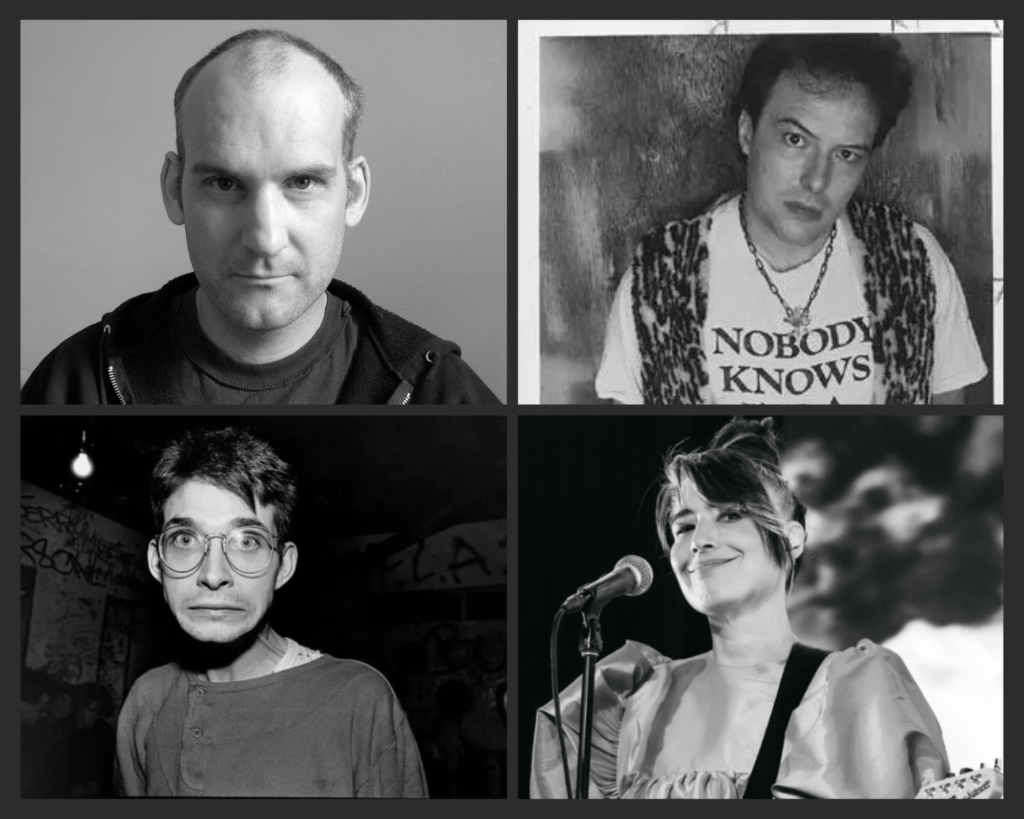

Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat and Fugazi is perhaps one of the most recognizable figures in the DIY world. His refusal to commodify the music experience—eschewing merchandise sales, maintaining low ticket prices, and rejecting traditional marketing—turned Dischord Records into a temple of independent ethics. He famously stated, “You don’t have to be a genius to do this. You just have to be sincere,” a quote that encapsulates the heart of DIY.

Jello Biafra, frontman of the Dead Kennedys and founder of Alternative Tentacles, merged satirical punk with radical politics. Through his label, he released albums that major companies wouldn’t touch, standing as a champion of free speech and dissent. His speeches and zine appearances often emphasized that DIY wasn’t about elitism but about empowerment through action.

Steve Albini, known for his abrasive sound with Big Black and later Shellac, brought his DIY ethic into the recording studio. As a producer, he made it clear that he worked for the bands—not the labels. Refusing royalties, Albini prioritized artist autonomy and openly criticized exploitative contracts, helping countless musicians maintain creative control.

Kathleen Hanna, the powerful voice behind Bikini Kill and the Riot Grrrl movement, used her platform to create space for women and marginalized voices in the punk world. Riot Grrrl’s DIY zines and meetups offered more than just music—they were avenues for education, self-expression, and activism. Hanna’s work emphasized that punk could be a safe space for those traditionally excluded.

These figures, and many others like them, transformed DIY from an underground curiosity into a cultural cornerstone. Their influence continues to ripple through generations of artists and fans.

Community Infrastructure, or How DIY Held Itself Together

Long before the convenience of digital platforms, DIY scenes functioned through grassroots infrastructure powered by human dedication and resourcefulness.

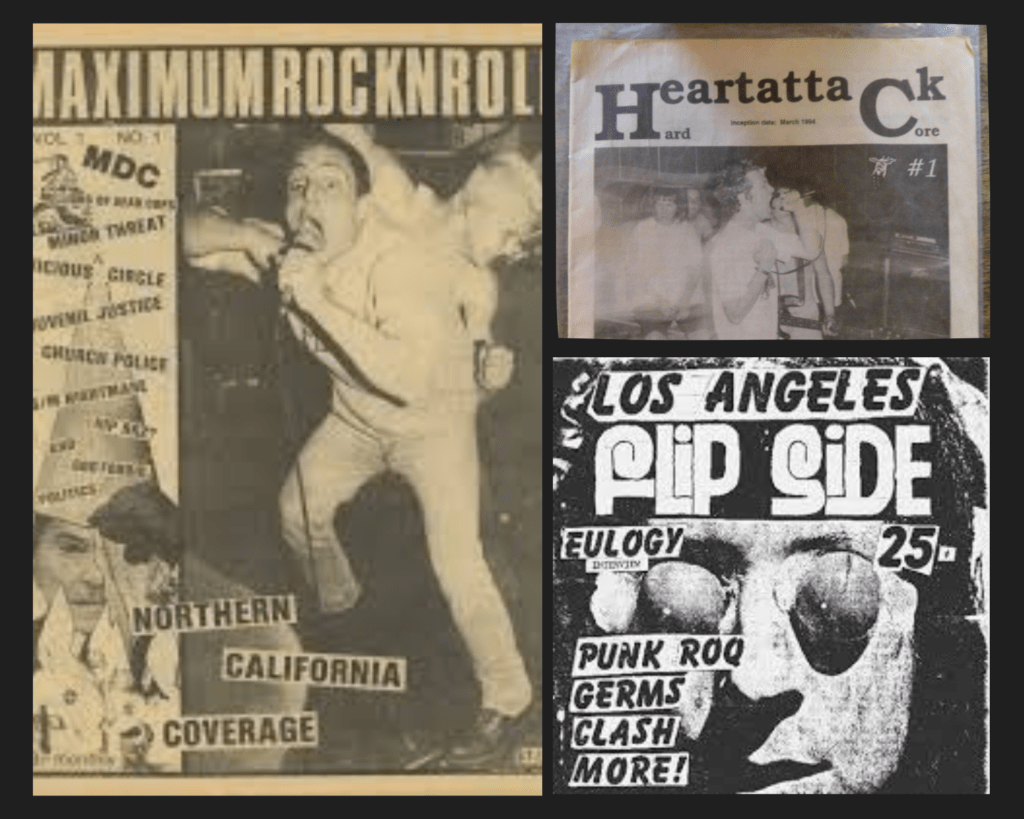

Zines were perhaps the most iconic element of early DIY culture. Publications like Maximum Rocknroll, Flipside, and HeartattaCk existed solely to provide information and spread the DIY word. These zines featured interviews, show reviews, political manifestos, and scene reports from around the world. They provided a tangible network for punks to connect, share ideas, and organize across vast distances.

Tour booking operated like an underground railroad of trust. Bands would rely on word-of-mouth networks to secure shows, places to sleep, and even meals. A contact in one city would pass on information to another in the next state, and so on, creating an informal yet reliable touring circuit built entirely on relationships and shared values.

With traditional venues often inaccessible, punks turned to DIY solutions. House shows became a rite of passage. Living rooms, garages, and basements transformed into intimate stages where bands performed inches away from their audience. Squats in Europe operated as autonomous cultural centers, offering not only performance spaces but also workshops, libraries, and communal kitchens.

Distribution of music also followed non-traditional paths. Before Bandcamp, there were distros—individuals or collectives who compiled catalogs of tapes, vinyl, patches, and zines. Fans would send handwritten letters with cash enclosed to receive music weeks later. Tape trading, especially in metal and hardcore circles, became a global practice. An Indonesian fan might hear a Finnish crust punk demo, thanks to this analog exchange.

This infrastructure wasn’t just about sharing music—it was about building resilient communities. Trust, solidarity, and mutual aid were the pillars that made this sprawling network work.

Global DIY in Action

The global reach of DIY music scenes proves that this movement was never confined to a single country or culture. In Indonesia, punk and hardcore took root in the 1990s, particularly in cities like Yogyakarta and Jakarta. Despite operating under a regime known for censorship and police crackdowns, local punks carved out their own spaces. When shows were raided, they found alternative locations—abandoned buildings, secluded fields, or even moving vehicles. This resilience only fueled their determination to keep the music and message alive.

During the siege of Sarajevo in the Bosnian War, the DIY ethos quite literally became a form of survival. Amid shelling and destruction, a small but committed punk and alternative scene continued to host shows in basements. Bands like SCH and Protest kept culture alive under siege, proving that even in the face of war, the human need for expression and connection through music could not be silenced.

In Tijuana, Mexico, the border punk scene grew into a cultural force that bridged two nations. Shows organized in makeshift venues attracted both local and international audiences. Spaces like Multiforo Alicia provided a haven for political expression, art, and independent music. The scene was deeply rooted in anti-authoritarianism, with many bands using their platform to critique both U.S. and Mexican policies.

The Philippines also boasts a vibrant DIY community, especially in cities like Manila. Collectives such as Food Not Bombs Philippines use punk shows to raise awareness and funds for social issues. Events often combine performances with food sharing, workshops, and grassroots organizing. This blend of activism and art continues to make punk more than just a genre—it becomes a platform for social change.

A Movement Under Pressure

As the digital era has expanded access to tools and audiences, it has also complicated the DIY approach. The internet, once hailed as a great equalizer, has now become a double-edged sword. While it’s never been easier to record, distribute, and promote music, the sheer saturation of content means that visibility is increasingly tied to metrics—likes, views, and shares—rather than authenticity or artistry.

Maintaining a digital presence now feels obligatory, with bands expected to maintain Instagram feeds, update TikTok content, and produce YouTube videos regularly. This constant churn of content can be draining, shifting the focus from community and creativity to brand management. For many artists rooted in DIY values, this shift is uncomfortable and disheartening.

Urban gentrification adds another layer of pressure. Across the globe, the closure of affordable, alternative venues has left many scenes homeless. Cities like San Francisco, Berlin, and London have seen the erosion of grassroots spaces due to rising rents and redevelopment. Places that once thrived on community-driven shows are now replaced with condominiums or boutique cafes. The same economic forces that once inspired DIY resistance are now making it harder to sustain.

International touring, once a rite of passage for underground bands, has become increasingly bureaucratic and expensive. Visa restrictions, travel costs, and political tensions often prevent bands—particularly from the Global South—from accessing audiences abroad. Meanwhile, Western bands with more resources still dominate global stages, perpetuating an imbalance even within DIY circles.

Despite these challenges, the DIY spirit continues to evolve. Artists are finding creative ways to adapt, whether by organizing digital festivals, embracing cooperative models, or leaning into local scenes with renewed energy. The foundation remains the same, even as the tools and terrain shift.

Reinventing the DIY Ethic for the 2020s

The future of DIY depends on adaptability and intention. Rather than resisting modern tools outright, many in the community are reimagining how to use them on their own terms. Platforms like Bandcamp and Big Cartel have become lifelines, allowing artists to sell music and merchandise directly to fans without corporate middlemen. These tools align with DIY values, enabling autonomy and fair compensation.

Independent labels have also evolved. Modern outfits like The Ghost Is Clear (Kansas City), Counter Intuitive Records (Massachusetts), and Dog Knights Productions (UK) carry the torch with a blend of tradition and tech-savviness. They often sign artists based on community fit and DIY spirit rather than marketability, and they engage in transparent practices that support musicians holistically.

Education and mentorship have emerged as crucial components. From home-recording tutorials to workshops on organizing inclusive shows, today’s DIY circles are placing a greater emphasis on knowledge-sharing. This not only ensures sustainability but also invites younger and more diverse participants into the fold, preserving the movement’s future.

As Ian MacKaye once said, “DIY is not a style of music, it’s a way of living.” This mindset continues to resonate, urging communities to build, adapt, and protect what matters most: independence, integrity, and solidarity.

DIY Will Never Die—It Will Adapt

DIY culture is alive, but it needs deliberate cultivation. As society grows more digital and disembodied, the power of real connection—rooted in self-made, community-driven culture—becomes ever more crucial.

This movement has always been more than chords and a chorus, it’s been about claiming space in a world that never offered any. And whether it’s in a basement in Helsinki, a squat in Jakarta, or a rooftop in Mexico City, the message remains the same:

Do it yourself. Do it together. And never let go.